The following article was printed in the Lincoln Journal Star on December 31, 2025:

The Stranger in the Grocery Aisle: When Sight Fades, Silence Shouldn't Follow

By: Tandi Perkins

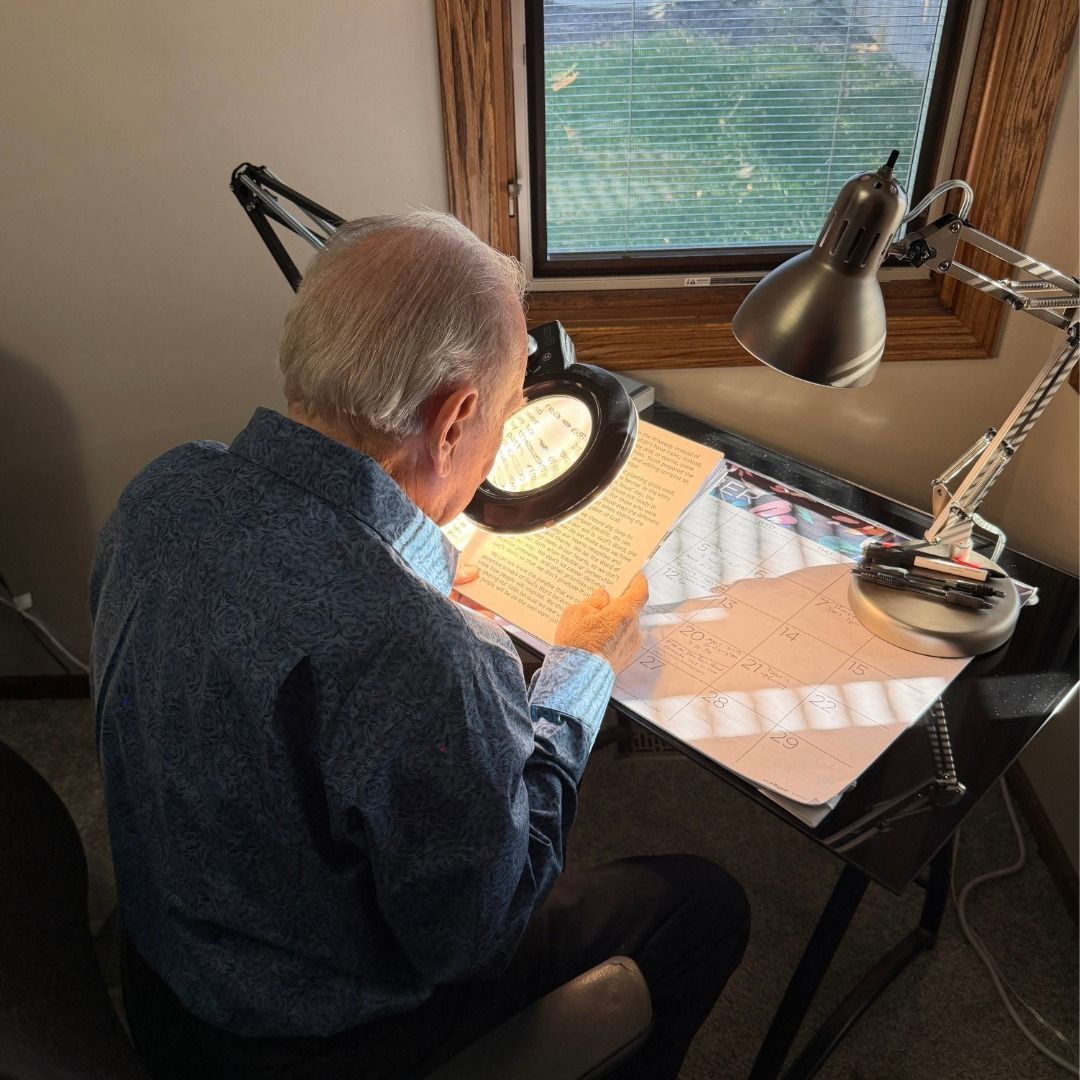

I watched my father surrender in the grocery aisle last week.

He was holding a can of soup, inching it closer to his face, trying to find the light that would let him read the label. He couldn't see it. But he didn't ask for help. He simply put the can back on the shelf and walked away empty-handed.

It was a small moment, but it broke my heart. In that soup aisle, I saw exactly where medicine ends and where the "Quiet Crisis" begins.

My father isn't "blind" in the way most people think. He is in the terrifying transition of losing his sight.

Glaucoma is slowly stealing his vision, but the isolation is taking his spirit. He surrendered in that aisle not because he couldn't see, but because he felt he had lost his dignity. He didn't want to be a burden. He retreated into the silence, convinced that the world he had navigated for decades was now closed to him.

This isn't a medical failure. It is a gap in our system.

We have world-class doctors in Lincoln. They treat diseases like Macular Degeneration, Glaucoma, and Diabetic Retinopathy with incredible skill. But for thousands of patients, there comes a day when the doctor has to say, "The vision loss is irreversible. There is nothing more we can do."

That transition—from patient to a person learning to live with low vision—is where the silence takes over.

The CDC reports that nearly 40,000 Nebraskans are living with blindness or severe vision impairment. For those navigating this transition, the isolation is just as dangerous as the disease. According to the CDC, 1 in 4 adults with vision loss suffers from anxiety or depression.

We are saving their eyes as long as we can, but we are losing their spirits when the treatments stop.

I work for Christian Record Services, an organization that has served this community from our Lincoln headquarters for 125 years. We serve everyone, regardless of faith or background. But watching my father has forced me to look in the mirror.

I realized that for too long, organizations like ours have focused on serving those who are already blind, often missing the people in the hardest part of the journey: the transition from sight to blindness.

Handing a lonely person a braille book or audio file doesn't help if they are still grieving the loss of their sight. They don't need a product; they need a guide.

My father didn't need a pamphlet in that grocery aisle. He needed to know that his life wasn't over just because his vision was fading. He needed to know there are tools, strategies, and a community that understands exactly what he is mourning.

This is the shift we are trying to make at our organization, but a non-profit cannot solve this alone. We need a shift in how we treat our neighbors.

To our medical community: You are the first line of defense. When the diagnosis is irreversible, help your patients find the community support that picks up where the prescription ends.

To my neighbors in Lincoln: The next time you see someone hesitating in the aisle, struggling to read a price tag or navigate a curb, don't just see a vision problem. See a neighbor fighting to stay part of the world.

We call Nebraska "The Good Life." Let’s work together to ensure that life remains good, even when the lights start to dim.